CROST: on the track of affordable tramways

Talk by Lewis Lesley

UCL 4th March 2009

Other ways to deliver tramways

For the last 50 years, when public transport has been in public ownership, the model for capital investments is that the funding comes from the Treasury and has to compete with other areas of public funding, e.g. health services, education, housing, defence etc.. Where public transport operates at a surplus, its public owner usually takes the profit to reduce rates or taxes. Usually public transport is been operated at a loss for political reasons, either as a means of creating employment, or having low fares. There is then no asset depreciation, or sinking fund, to provide an alternative source for capital investment.

Prior to public ownership, public transport was provided by the private sector. All the UK railway network and most of the London tube system was built with private investments. Perhaps the period of public ownership may be seen as a historic blip ? In private operation, all bus companies and rail operators in London, not only does the operation have to be managed efficiently, but that sufficient surplus must be maintained to allow assets, e.g. vehicles, to be refurbished or replaced to maintain market share, and therefore revenue stream.

The historic model for a private tramway scheme is a group of local business leaders coming together, setting up a company to improve their local area, investing in it themselves, and raising the balance of the funds needed to build, commission and operate the tramway. Some of the initial investors would be the Directors of the company, employing professionally qualified staff to manage and operate the system. There are still examples of this in other areas of economic activity, so it can be re-activated for new trams. The big difference now is that in many cities, like London, there are also several tiers of public authorities with planning, transportation and regulatory powers. Gaining approval from these bodies can take as much or more time, as the actual construction and commissioning of the tramway. An example of cost for a new two line tramway, 21km long, needing 17 tramcars in another EU country is shown in Table. 9.

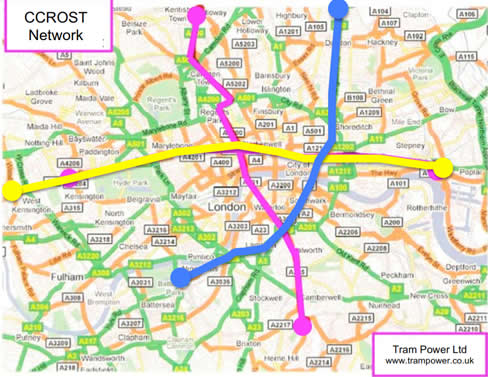

Outline of the CROST network

TABLE 9 Tramway Capital Costs

| Capital Item | Cost €millions |

| Tram tracks | 53 |

| OHL | 15 |

| Sub Stations | 6 |

| Tram stops | 15 |

| Depot | 15 |

| Utilities | 11 |

| Renewable Generation | 15 |

| Traffic management | 5 |

| Tramcars | 35 |

| Contingency | 30 |

| TOTAL | 200 |

|---|

If this cost structure were applied to the CROST proposal, it would cost a total of about £300million. Similarly if the NAO criticism is applied to the TfL cost estimate for Cross River Line in 2006, it should really be £325million.

| Home |

| Introduction |

| Central London |

| NAO Report |

| Costs Too High |

| Reducing Costs |

| Finance |

| Other Ways |

| Conclusion |

| Links |

| Contact Us |

| FAQ |

|

| Copyright © 2012 London Tram. All rights reserved. |

|

Site design by WEBWIZARDS |

||

| This web site is W3C compliant | ||||